How should we shape the future of life?

Today, we continue our series of blogs looking at public views on the four themes that guide our work. A quick reminder of these themes:

- Climate and Environment: How can we live sustainably?

- Data, AI and Robotics: How should we shape our digital world?

- Health, Ageing and Wellbeing: How should we live healthy lives?

- Life Sciences and Biotechnology: How should we shape the future of life?

We started a couple of weeks ago with a look at the public values and views that are common across all dialogues, regardless of the specific theme. We’ve looked at how we can live sustainably and how we can live healthy lives. Today, our focus is on dialogues that explore how we should shape the future of life.

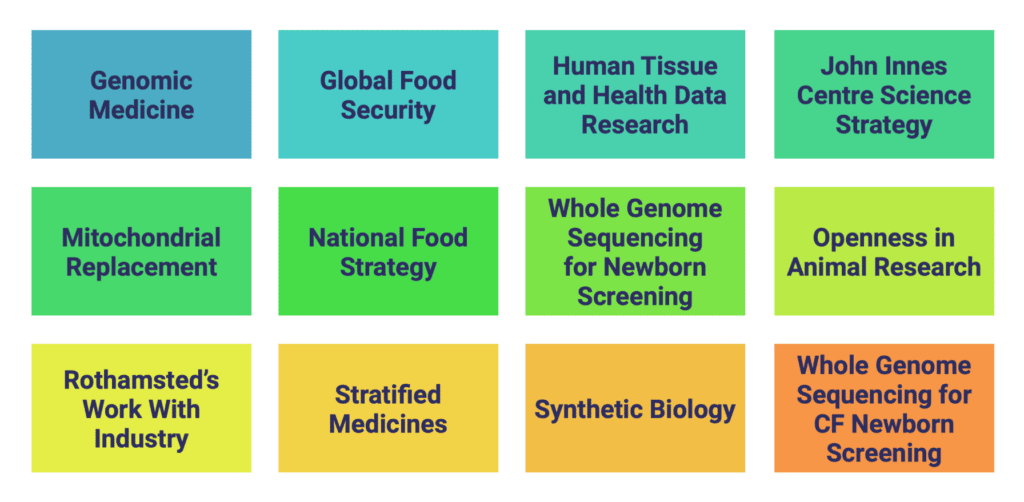

In some ways, all Sciencewise dialogues look at how we shape the future of life. All of our dialogues inform decisions or research that will impact our futures. But today, we’re looking at a set of specific dialogues that address topics in the life sciences and biotechnology. Very crudely, life sciences might be defined as the theoretical and systematic study of living organisms, whilst biotechnology refers to a broad range of technologies that use organisms – or parts of organisms – to make tools, processes or products.

Biotechnology and the life sciences can raise big ethical questions and participants often explore the values and principles that underlie their views, as well as their views themselves. Four themes arise across the twelve dialogues we have run in this area:

1. The benefits from life sciences and biotechnologies should be distributed equitably

Participants acknowledge that there is a role for private sector involvement in the life sciences and biotechnology, and a potential for benefits to large numbers of people. However, as happens across all of our dialogues, people raise concerns about the impact of new technologies on inequality. They’re concerned about exacerbating existing inequalities, or creating new ones. The profit motive is seen as contributing to unequal outcomes of both life science research and access to biotech supported services, and at odds with the principles of universal healthcare as a public good. People want treatments and procedures to be available on the NHS and free at the point of delivery.

The concern about inequality is true for all stages in the policy cycle. Whether it’s defining the problem, identifying the solution, implementation, or evaluation, people want to ensure that we recognise potential inequalities and ensure these are reduced. They don’t want access to the benefits of a new technology to be unequal. And, they express inequality in financial terms. For example, participants worried that existing social divisions could worsen if wealthy people can pay for human augmentation whilst those who are less wealthy can not. But they worry about ethnicity, expressing concern about things like genomic screening being tailored to White people, with people from ethnic minority groups being under-served. It’s not just human biotech and life sciences that raise the fear of unequal and unfair outcomes. People are similarly concerned about technologies used in agriculture. They worry about the affordability of food and its impact on their health, identifying a trade-off faced by people on lower incomes who have to choose between more nutritious and more affordable food. This was seen as a vicious cycle which would widen the gap between rich and poor.

2. Businesses must contribute to the public good and adhere to red lines

People are broadly ok with private businesses being involved in researching and developing life sciences and biotechnologies. But, as in other dialogues, they are not comfortable with excessive profiteering in this field and want to see clear roles set out for businesses which prioritise public benefit. They also set out clear red lines which businesses should not cross, such as selling human data to insurance or marketing companies. They are also concerned about how profit might affect the choice of research area, with potential less commercial ventures being neglected. In such cases, they thought that public institutions should work for public good, ensuring that treatments are developed even if these are not commercially viable.

Despite these concerns, participants do think that public good can result from private sector involvement in research with the potential to benefit a lot of people or people vulnerable to specific diseases. Defining public good is difficult, and participants struggled with this. Broadly, it is seen as something that positively impacts people’s lives. Sometimes, they defined it negatively, in terms of what it would prevent – for example, dystopian futures created by misuse of genomic science.

3. Robust governance structures must be in place

To realise the range of potential public benefits arising from life science and biotechnologies, people want to see robust and effective regulation.

Participants think that policymakers and regulators have an essential role in long-term thinking about how different sciences and technologies could benefit society generally. This includes how to prevent minority groups being discriminated against by the development and use of these sciences and how the private sector can help to achieve those public goods. They want to see long-term planning that links up the science of research and development with the social reality of people’s lives through public engagement so that the former can be informed by and benefit the latter.

4. Individual agency is important

Looking at specific therapies, treatments and screening procedures that are already developed, people tend to focus on individual agency. For example, while participants saw licensing mitochondrial replacement therapy for clinical use as a positive development, they also think that individuals should be able to choose whether to use the technology or not. Similarly, looking at approaches that create new cells or redesign existing cells to carry out new tasks, dialogue participants think that individual consent should always take precedence.

Conclusions

The research, development and rollout of any life science and biotechnology is seen by the public as carrying significant potential benefits and risks. People are concerned that innovations will exacerbate and create new inequalities, and that the pursuit of profit might negatively impact who the innovations are for and who has access to them. However, they see an important role for the private sector in developing the science and technology in this area, providing that robust regulation is in place to ensure that societal benefits are secured and that the public’s concerns are mitigated against. And (insert something about one of the benefits)

Two risks are seen as being of particular significance and are expressed throughout dialogues. First, that innovation will exacerbate and create new inequalities and that that private interests and the pursuit of profit might negatively shape how life sciences and biotechnologies are developed, including who they are designed to benefit and who has access to them.

However, the public does see an important role for the private sector in developing the science and technology in this area, providing that robust regulation is in place to ensure that societal benefits are secured and that the public’s concerns are mitigated against. Governance should connect science and technology in a meaningful way with the social reality of people’s lives.

Read our full report that draws together findings from multiple Sciencewise dialogues conducted over the last decade in relation to the Health and Wellbeing here.

Take a look at our Projects and Impacts page if you’d like to find out more about some of our previous dialogues. And to hear more about the impact that public participation can have on participants, see here.